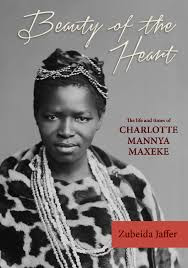

On black excellence: Charlotte Mannya Maxeke

I’ve been reading Zubeida Jaffer’s biography of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, Beauty of the Heart. I was very excited at the prospect of finally having a book available about a woman who is mostly known through the hospital that is named after her in Johannesburg. Beyond the hospital naming, I doubt she is a household name. I discovered her story when I was doing my Honours, and researching Nontsizi Mgqwetho’s poetry. A friend (who was doing her Masters on Tiyo Soga and Nonstizi Mgwetho) and I became obsessed with finding out more about 19th century African intellectuals. I came across the website New African Movement and discovered names such as Sol Plaatjie (who was a contemporary of Maxeke’s), D.D.T. Jabavu, A. B. Xuma but admittedly very few black women who had a public life and reputation in the late 1800s and 1900s.

|

| The cover of Zubeida Jaffer's biography |

Maxeke’s story is an extraordinary one. She graduated from Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1901 and became the first black woman in South Africa to obtain a university degree—a BSc nogal! It is significant that she went to Wilberforce given its history as the oldest historically black university in the United States of America, established in 1863. Maxeke joined the university almost by fluke. She had been part of a travelling choir which had travelled to Great Britain to sing for Queen Victoria and moved onto America. When the choir was abandoned by their English managers due to financial difficulties, Maxeke’s plight “attracted the attention of ministers of the African Methodist Episcopalian Church who came to their rescue” Jaffer explains in the biography. She further explains the university at the time as “the cultural and academic centre of the African-American intelligentsia. Charlotte was directly exposed to the thinking of the renowned sociologist and political thinker, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois and to other differing strains of thought. The young Du Bois was Charlotte’s teacher at Wilberforce.” Reading Du Bois’s work and imagining Charlotte as his student one can only be envy-ridden. The experience of being amongst black people who were no longer slaves and who took hold of that by creating their own university gives us a sense of Charlotte’s own identity formation as someone who was from a fast-changing South Africa with the Anglo-Boer brewing back home.

In 1930 Dr A.B.Xuma wrote an essay about Maxeke: “Charlotte Manye(Mrs Maxeke): What an educated African girl can do” in order to make “an argument for higher education of our African women.” The forward to the essay was written by Du Bois who describes Maxeke as someone who has a “clear mind, [a] fund of subtle humour and a straight-forward honesty [of] character”. He further explains “I regard Mrs Maxeke as a pioneer in one of the greatest of human causes, working under extraordinarily difficult circumstances to lead a people, in the face of prejudice, not only against her race, but against her sex. To fight not simply the natural and inherent difficulties of education and social uplift, but to fight with little money and little outside aid was indeed a tremendous task”. This writing is further evidence of not only Maxeke’s context but her character as well. Maxeke’s accomplishments and work are extensive and everyone should read Dr Xuma’s essay for themselves in order to fully grasp the importance of Maxeke’s legacy. Her most significant being the establishment of the Bantu Women’s League “for the protection of African Women’s rights” which petitioned against pass books. Apart from Jaffer’s recent book I have only come across Thozama April’s PhD thesis which looks at Maxeke’s political contributions in the 19thcentury. After reading Dr April’s thesis a friend sent me three of Maxeke’s essays titled: “The progress of native womanhood in South Africa”, “The city mission” and “Social conditions amongst Bantu women and girls”. Glancing at the titles alone one can already see the formidability in Maxeke’s voice. The silence and erasure about Maxeke’s life is a travesty.

|

| The portrait of an older Charlotte Mannya Maxeke |

Since ‘discovering’ Charlotte Mannya Maxeke I have been able to stand a little taller. In a world that cares very little for the internal world and lived experience of black women, Maxeke’s story matters. Not so long ago black women were seen as minors who had to get permission from the adult males in their families to do something as simple as travelling. In her autobiography, Call me woman, Ellen Khuzwayo tells of a humiliating moment where she had to get her son’s permission to get a passport and travel. This is significant because even at a time like 2016 where black women are able to speak up for themselves, we still share experiences where we are silenced, bullied and infantilised because there is very little space for black women to simply be. I have written about the representation of the black women who are climbing the corporate ladder of success. These stories are a reflection of what is possible when women are given the space to rise; but I also hope they highlight the dangers of exceptionalism that is part of this narrative. The reality for most black women is that most are unemployed, dealing with poverty and violence.

I don’t know how Charlotte Maxeke and the women she worked with in the 19th century trying to establish the Bantu Women’s League would feel about the position of black women today. For me Maxeke is the original example of “black girl magic”. Many young black women across the world have had to confront their lived experienced and some have latched onto “black girl magic” as a way of finding a community of black women who celebrate their successes and share experiences that affirm them. One such example in South Africa is the For Black Girls Only event which was mired in debate over whether black women were being racist for demanding a space where only black women are allowed. I attended the event and loved every minute of it and ignored the haters who didn’t want to have to deal with the expression of what it means to be young, black and a woman in South Africa.

The truth is many young black girls do not know Charlotte Maxeke’s story. And there’s a danger in this. I’ve been told I am ambitious (which I don’t think is true) simply because I studied further than some people. Studying further was not unusual for me because I was and am still surrounded by incredibly intelligent, black women who have done the same. For me, it was normal that I should make use of the opportunity to study further. And Charlotte Maxeke’s story reminds me that the experiences I have and hope to have are normal for a black woman. Charlotte Maxeke’s story reminds me that I can create the reality I want; I don’t have to respond to the small space that is created for black women to occupy. Whenever I face backlash for being outspoken about the black experience I return to Charlottle Mannya Maxeke’s words and story as a reminder that “my soul’s intact” (from Nina Simone’s song “young gifted and black”, inspired by Lorraine Hansberry’s work) and that my world is alright.

|

| A sketch version of the picture which appears on the cover of Zubeida Jaffer's book. This image is taken from the portraits of the choir which travelled to Great Britain in 1891. |

Comments