Women who made history: Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho

In preparation for the Maxeke-Mgqwetho Annual Lecture and Masterclass, I spoke at St Mary's School which will be hosting the two events. Below is the message which I shared with the girls in the chapel services. There were two readings in the service: a poem "Mayibuye iAfrika" by Nontsizi Mgqwetho as well as the gospel reading: Matthew 28:1-10.

Today’s gospel reading is about women who made history; which is intricately linked to the two women I’d like to introduce to you. In the gospels we read about women being the first people to go and find Jesus’ body after the crucifixion. Much has been said about this scripture because it opens up the conversation about the role of women in the story of Jesus. In fact, many have written that without the two Mary’s Christianity would not have been established because it is the women who are the first to discover the resurrection. Without the resurrection, the story of Jesus, the promise of the risen Christ would not have been verified. And so it matters that the people who find the empty tomb and meet the angel who confirms that Christ has risen are the two Marys: Mary Magdalene and Mary, the mother of James and Salome.

It is important to note that what these women were doing—going to find Jesus—was potentially life threatening. In Matthew 27 we read about the tomb being guarded because the chief priests and the Pharisees suggested that the tomb be guarded because they thought that the disciples would come and steal Jesus’s body so that they can fake the resurrection. So Pontius Pilate says “go, make the tomb secure as you know how…and the guards made the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting a guard”. So in a sense, the women were doing something potentially illegal if we think about the political context of Jesus’ death. And so, the fact that the disciples aren’t the ones who go find Jesus tells us about the level of fear amongst the disciples because of the nature of Jesus’ death. And if you are ever interested in the politics of the death of Jesus read the book Zealot by Reza Aslan. So the question I ask myself when I read this story is: why were the women unafraid of going to the tomb? Asked another way, why were these women unafraid of making history?

I found it very interesting that each of the gospels give a slightly different account of what the women experienced when they arrived at the tomb. This is the consequence of the way in which the gospels were written and it often helps me to think about the Bible as a historical document which has tried to mark the moments of Christ. What is interesting is the ways in which the Mary’s are introduced in the story. In Matthew we read about Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, in Mark we read about Mary Magdelene and Mary the mother of James and Salome, in Luke we only get the women’s names in verse 10 as though their names are not important in the story and in John only Mary Magdelene is mentioned. And in each account, the disciples hear about Jesus from the women. This is significant because it mirrors the ways in which history is recorded and the implications it has for women. Because of the ways in which history has been recorded by men who wanted to tell their own version of the story and remain in power, the stories about women are often misrepresented or erased completely. The ways in which we have been taught to believe about the role of women in history is such that their names don’t matter or they are not recorded at all. Luckily for the two Marys they went to the tomb; if they hadn’t gone to the tomb, we would probably not know the extent of the relationship they had with Jesus. And so it seems that in order for women not to be forgotten we have to accept that we must be unafraid, or perhaps not overthink danger in the same way the two Marys took it upon themselves to go to the tomb and do what seems to be a basic tradition of putting oil and spices on Jesus’ body. So instead, they were making history.

These two Marys remind me of many other women across history whose names I am finally beginning to find in order to make sense of my own life but also to make sense of history. Like the two Marys, there are two women in South Africa’s history whose names are not as famous as they should be. Their names are Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho. We know very little about Nonstizi Mgqwetho’s life until she enters the social scene in the 1920s as a poet who wrote in isiXhosa in Umteteli Wabantu, a popular newspaper in the 1920s. Her poems were collected over time and in 2007 a book of her poems and translations into English was finally published.

Charlotte Maxeke is a little more well-known than Nontsizi Mgqwetho. She had a seemingly normal childhood for a black child in the 1800s but her life changed when she met her two teachers Paul Xiniwe and Isaac Wauchope. Both these teachers were influential in Charlotte’s life and saw her potential. They were themselves influential characters in South Africa’s history. Isaac Wauchope was a writer and Paul Xiniwe was a musician who was involved in the establishment of the African Choir which toured Britain in 1891 and performed in front of Queen Victoria which Charlotte Maxeke was a part of when she 22 years old. In 1894 she travelled with the choir to America where they performed until the bad financial management of the choir masters caught up with them. It was an advert in a newspaper which changed Charlotte’s life as she was able to stay in America and study at Wilberforce University in Ohio with the help of the African Methodist Episcopalian Church which funded her studies. This meant that she became the first black woman to get a university degree abroad graduating in 1901. This matters because at the time, in South Africa, there were few opportunities for women to study, let alone study and get a degree, so for Charlotte to get a degree abroad, matters in ways we cannot imagine given our relationship with studying further. There were also other black South African students studying abroad at the time. Many of them returned to South Africa to play a historical role which changed the life and politics of South Africa.

When Charlotte returned to South Africa after graduating, she did not disappear into a quiet life; she became a social activist. She was married to a newspaper man whom she had met at Wilberforce and the two of them set about writing and talking about the politics of their time. Her connections at Wilberforce University also led to the establishment of the South African chapter of the African Methodist Espicopalian Church. In 1918, Charlotte established one of the first women’s organisations called the Bantu Women’s League.

I like to imagine that these two women were friends. But we don’t have enough information about them to make this conclusion. What we do know is that they knew about each other and admired each other’s work deeply. In her poetry Nontsizi wrote about how inspired she was by Charlotte Maxeke’s work. In an article Charlotte Maxeke wrote lambasting the political shenanigans of the men the organisation the SANNC which later became the ANC, she wrote about how inspired she was by the sharp political poetry of a woman whose voice has been silenced, she was writing about Nontsizi.

Like the two Marys in the bible, Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho wrote themselves into history as though they knew that if they did not write about their work and write about what they saw around them, no one else would do it. It was Charlotte’s interest in music which led her to another country which changed her life. It was Nontsizi’s poetry which we have access to even today that allows us the opportunity to think about what does it mean to be women who speak about the things which hurt us, which undermine us and which do not uphold our humanity.

The stories of Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho are important not only for us as women, but they are important about what it means to be citizens in this country. I will end off with the poem which invokes the names of more women whom we are yet to write about and whose stories we are yet to hear. The title of the poem is Tongues of their Mothers by Makhosazana Xaba:

I wish to write an epic poem about Sarah Baartman,

one that will be silent on her capturers, torturers and demolishers.

It will say nothing of the experiments, the laboratories and the displays

or even the diplomatic dabbles that brought her remains home,

eventually.

This poem will sing of the Gamtoos Valley holding imprints of her

baby steps.

It will contain rhymes about the games she played as a child,

stanzas will have names of her friends, her family, her community.

It will borrow from every single poem ever written about her,

conjuring up her wholeness: her voice, dreams, emotions and thoughts.

I wish to write an epic poem about uMnkabayi kaJama Zulu,

one that will be silent on her nephew, Shaka, and her brother,

Senzangakhona.

It will not even mention Nandi. It will focus on her relationship

with her sisters Mawa and Mmama, her choice not to marry,

her preference not to have children and her power as a ruler.

It will speak of her assortment of battle strategies and her charisma as a

leader.

It will render a compilation of all the pieces of advice she gave to men

of abaQulusi who bowed to receive them, smiled to thank her,

but in public never acknowledged her, instead called her a mad witch.

I wish to write an epic poem about Daisy Makiwane,

one that will be silent on her father, the Reverend Elijah.

It will focus on her relationship with her sister Cecilia

and the conversations they had in the privacy of the night,

how they planned to make history and defy convention.

It will speak the language of algebra, geometry and trigonometry,

then switch to news, reports, reviews and editorials.

It will enmesh the logic of numbers with the passion that springs from

words,

capturing her unique brand of pioneer for whom the country was not

ready.

I wish to write an epic poem about Princess Magogo Constance Zulu,

one that will be silent on her son, Gatsha Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

It will focus on her music and the poetry in it,

the romance and the voice that carried it through to us.

It will describe the dexterity of her music-making fingers

and the rhythm of her body grounded on valleys,

mountains and musical rivers of the land of amaZulu.

I will find words to embrace the power of her love songs

that gave women dreams and fantasies to wake up and hold on to

and a language of love in the dialect of their own mothers.

I wish to write an epic poem about Victoria Mxenge,

one that will be silent on her husband Griffiths.

It will focus on her choice to flee from patients, bedpans and doctors.

This poem will flee from the pages and find a home in the sky. It will

float below the clouds, automatically changing fonts and sizes

and translating itself into languages that match each reader.

It is a poem that will remind people of Qonce

that her umbilical cord fertilized their soil.

It will remind people of uMlazi that her blood fertilized their soil.

It will remind her killers that we shall never, ever forget.

I wish to write an epic poem about Nomvula Glenrose Mbatha,

one that will be silent on my father, her husband Reuben Benjamin Xaba.

It will focus on her spirit, one that refused to fall to pieces,

rekindling the fire she made from ashes no one was prepared to gather.

This poem will raise the departed of Magogo, Nquthu,

Mgungundlovana,

iNanda, Healdtown, Utrecht, kwaMpande, Ndaleni and Ashdown,

so that they can sit around it as it glows and warm their hands

while they marvel at this fire she made from ashes no one was prepared

to gather.

These are just some of the epic poems I wish to write

about women of our world, in the tongues of their mothers.

I will present the women in forms that match their foundations

using metaphors of moments that defined their beings

and similes that flow through our seasons of eternity.

But I am not yet ready to write these poems.

|

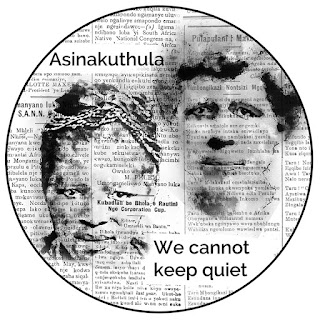

| Images of Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho |

Today’s gospel reading is about women who made history; which is intricately linked to the two women I’d like to introduce to you. In the gospels we read about women being the first people to go and find Jesus’ body after the crucifixion. Much has been said about this scripture because it opens up the conversation about the role of women in the story of Jesus. In fact, many have written that without the two Mary’s Christianity would not have been established because it is the women who are the first to discover the resurrection. Without the resurrection, the story of Jesus, the promise of the risen Christ would not have been verified. And so it matters that the people who find the empty tomb and meet the angel who confirms that Christ has risen are the two Marys: Mary Magdalene and Mary, the mother of James and Salome.

It is important to note that what these women were doing—going to find Jesus—was potentially life threatening. In Matthew 27 we read about the tomb being guarded because the chief priests and the Pharisees suggested that the tomb be guarded because they thought that the disciples would come and steal Jesus’s body so that they can fake the resurrection. So Pontius Pilate says “go, make the tomb secure as you know how…and the guards made the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting a guard”. So in a sense, the women were doing something potentially illegal if we think about the political context of Jesus’ death. And so, the fact that the disciples aren’t the ones who go find Jesus tells us about the level of fear amongst the disciples because of the nature of Jesus’ death. And if you are ever interested in the politics of the death of Jesus read the book Zealot by Reza Aslan. So the question I ask myself when I read this story is: why were the women unafraid of going to the tomb? Asked another way, why were these women unafraid of making history?

I found it very interesting that each of the gospels give a slightly different account of what the women experienced when they arrived at the tomb. This is the consequence of the way in which the gospels were written and it often helps me to think about the Bible as a historical document which has tried to mark the moments of Christ. What is interesting is the ways in which the Mary’s are introduced in the story. In Matthew we read about Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, in Mark we read about Mary Magdelene and Mary the mother of James and Salome, in Luke we only get the women’s names in verse 10 as though their names are not important in the story and in John only Mary Magdelene is mentioned. And in each account, the disciples hear about Jesus from the women. This is significant because it mirrors the ways in which history is recorded and the implications it has for women. Because of the ways in which history has been recorded by men who wanted to tell their own version of the story and remain in power, the stories about women are often misrepresented or erased completely. The ways in which we have been taught to believe about the role of women in history is such that their names don’t matter or they are not recorded at all. Luckily for the two Marys they went to the tomb; if they hadn’t gone to the tomb, we would probably not know the extent of the relationship they had with Jesus. And so it seems that in order for women not to be forgotten we have to accept that we must be unafraid, or perhaps not overthink danger in the same way the two Marys took it upon themselves to go to the tomb and do what seems to be a basic tradition of putting oil and spices on Jesus’ body. So instead, they were making history.

These two Marys remind me of many other women across history whose names I am finally beginning to find in order to make sense of my own life but also to make sense of history. Like the two Marys, there are two women in South Africa’s history whose names are not as famous as they should be. Their names are Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho. We know very little about Nonstizi Mgqwetho’s life until she enters the social scene in the 1920s as a poet who wrote in isiXhosa in Umteteli Wabantu, a popular newspaper in the 1920s. Her poems were collected over time and in 2007 a book of her poems and translations into English was finally published.

Charlotte Maxeke is a little more well-known than Nontsizi Mgqwetho. She had a seemingly normal childhood for a black child in the 1800s but her life changed when she met her two teachers Paul Xiniwe and Isaac Wauchope. Both these teachers were influential in Charlotte’s life and saw her potential. They were themselves influential characters in South Africa’s history. Isaac Wauchope was a writer and Paul Xiniwe was a musician who was involved in the establishment of the African Choir which toured Britain in 1891 and performed in front of Queen Victoria which Charlotte Maxeke was a part of when she 22 years old. In 1894 she travelled with the choir to America where they performed until the bad financial management of the choir masters caught up with them. It was an advert in a newspaper which changed Charlotte’s life as she was able to stay in America and study at Wilberforce University in Ohio with the help of the African Methodist Episcopalian Church which funded her studies. This meant that she became the first black woman to get a university degree abroad graduating in 1901. This matters because at the time, in South Africa, there were few opportunities for women to study, let alone study and get a degree, so for Charlotte to get a degree abroad, matters in ways we cannot imagine given our relationship with studying further. There were also other black South African students studying abroad at the time. Many of them returned to South Africa to play a historical role which changed the life and politics of South Africa.

When Charlotte returned to South Africa after graduating, she did not disappear into a quiet life; she became a social activist. She was married to a newspaper man whom she had met at Wilberforce and the two of them set about writing and talking about the politics of their time. Her connections at Wilberforce University also led to the establishment of the South African chapter of the African Methodist Espicopalian Church. In 1918, Charlotte established one of the first women’s organisations called the Bantu Women’s League.

I like to imagine that these two women were friends. But we don’t have enough information about them to make this conclusion. What we do know is that they knew about each other and admired each other’s work deeply. In her poetry Nontsizi wrote about how inspired she was by Charlotte Maxeke’s work. In an article Charlotte Maxeke wrote lambasting the political shenanigans of the men the organisation the SANNC which later became the ANC, she wrote about how inspired she was by the sharp political poetry of a woman whose voice has been silenced, she was writing about Nontsizi.

Like the two Marys in the bible, Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho wrote themselves into history as though they knew that if they did not write about their work and write about what they saw around them, no one else would do it. It was Charlotte’s interest in music which led her to another country which changed her life. It was Nontsizi’s poetry which we have access to even today that allows us the opportunity to think about what does it mean to be women who speak about the things which hurt us, which undermine us and which do not uphold our humanity.

The stories of Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho are important not only for us as women, but they are important about what it means to be citizens in this country. I will end off with the poem which invokes the names of more women whom we are yet to write about and whose stories we are yet to hear. The title of the poem is Tongues of their Mothers by Makhosazana Xaba:

I wish to write an epic poem about Sarah Baartman,

one that will be silent on her capturers, torturers and demolishers.

It will say nothing of the experiments, the laboratories and the displays

or even the diplomatic dabbles that brought her remains home,

eventually.

This poem will sing of the Gamtoos Valley holding imprints of her

baby steps.

It will contain rhymes about the games she played as a child,

stanzas will have names of her friends, her family, her community.

It will borrow from every single poem ever written about her,

conjuring up her wholeness: her voice, dreams, emotions and thoughts.

I wish to write an epic poem about uMnkabayi kaJama Zulu,

one that will be silent on her nephew, Shaka, and her brother,

Senzangakhona.

It will not even mention Nandi. It will focus on her relationship

with her sisters Mawa and Mmama, her choice not to marry,

her preference not to have children and her power as a ruler.

It will speak of her assortment of battle strategies and her charisma as a

leader.

It will render a compilation of all the pieces of advice she gave to men

of abaQulusi who bowed to receive them, smiled to thank her,

but in public never acknowledged her, instead called her a mad witch.

I wish to write an epic poem about Daisy Makiwane,

one that will be silent on her father, the Reverend Elijah.

It will focus on her relationship with her sister Cecilia

and the conversations they had in the privacy of the night,

how they planned to make history and defy convention.

It will speak the language of algebra, geometry and trigonometry,

then switch to news, reports, reviews and editorials.

It will enmesh the logic of numbers with the passion that springs from

words,

capturing her unique brand of pioneer for whom the country was not

ready.

I wish to write an epic poem about Princess Magogo Constance Zulu,

one that will be silent on her son, Gatsha Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

It will focus on her music and the poetry in it,

the romance and the voice that carried it through to us.

It will describe the dexterity of her music-making fingers

and the rhythm of her body grounded on valleys,

mountains and musical rivers of the land of amaZulu.

I will find words to embrace the power of her love songs

that gave women dreams and fantasies to wake up and hold on to

and a language of love in the dialect of their own mothers.

I wish to write an epic poem about Victoria Mxenge,

one that will be silent on her husband Griffiths.

It will focus on her choice to flee from patients, bedpans and doctors.

This poem will flee from the pages and find a home in the sky. It will

float below the clouds, automatically changing fonts and sizes

and translating itself into languages that match each reader.

It is a poem that will remind people of Qonce

that her umbilical cord fertilized their soil.

It will remind people of uMlazi that her blood fertilized their soil.

It will remind her killers that we shall never, ever forget.

I wish to write an epic poem about Nomvula Glenrose Mbatha,

one that will be silent on my father, her husband Reuben Benjamin Xaba.

It will focus on her spirit, one that refused to fall to pieces,

rekindling the fire she made from ashes no one was prepared to gather.

This poem will raise the departed of Magogo, Nquthu,

Mgungundlovana,

iNanda, Healdtown, Utrecht, kwaMpande, Ndaleni and Ashdown,

so that they can sit around it as it glows and warm their hands

while they marvel at this fire she made from ashes no one was prepared

to gather.

These are just some of the epic poems I wish to write

about women of our world, in the tongues of their mothers.

I will present the women in forms that match their foundations

using metaphors of moments that defined their beings

and similes that flow through our seasons of eternity.

But I am not yet ready to write these poems.

Comments